If the automobile is emblematic of mankind’s innate desire for autonomy and independence, the phone represents our powerful need to connect with one another. Combine these two seemingly diametrically opposed technologies into one and you get: The car phone the phone car the car phone. It's an idea that has been around a lot longer than you might think.

How long, exactly? The photo up top dates from January 1946; it shows Frederick T. Budelman of the Fred. M. Link Corp. demonstrating a “radio dial telephone system” mounted in what appears to be a Chrysler. A separate set of systems, operated by Bell, went live in St. Louis and Chicago in June and October of that year.

Take a look at this Bell promotional video from the late 1940s to get a feel for what this incredible cutting-edge technology was like:

Motorola offered two-way car radios as early as 1939, primarily for public safety use. Operating on the AM band, these were a little like souped-up walkie-talkies in that they operated entirely over radio frequencies. Car-based radiotelephones worked a little bit differently, and the hammy film above gives a good overview (really, it’s worth a watch).

The Bell MTS showcased is actually two separate, but related, systems for two different use cases. The first is designed to let individuals phone vehicles moving along the highway system. In the film, a dispatcher for a cartage operation calls two of his company’s drivers in the field, directing them to make an extra stop to fill some empty space in their tractor trailer. The second lets anyone within an urban area use their car phone to call a landline number; we’re shown how a construction company foreman can call in from the ever-expanding suburban frontier to get parts for a busted earthmover, stat.

In both cases, the system used a vehicle-based VHF transmitter/receiver to make contact with radio towers that are in turn connected to the hard-wired telephone system. In the first example, these towers are spaced at regular intervals along highway systems (so the hypothetical dispatcher would need to know, roughly, which generically named American city his men were driving past at that moment—Centerville, in this case). In the second, the man in the field simply needed to be within reach of an area’s radio network to call home base.

Either way, the whole thing was handled through operators working switchboards. Cool!

This page here goes into extensive historical and technical detail about the system and includes pictures of some of the equipment. A Western Electric in-cabin control unit would be the ultimate period accessory for an early postwar car, especially if you could figure out how to modify it for use it as a cellphone accessory—you could even use your smartphone’s built-in voice command functionality to dial in lieu of a sassy switchboard operator (sassy switchboard operators being, sadly, in short supply these days).

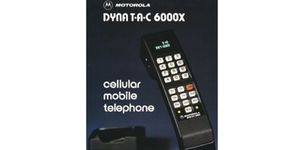

Unlike the mobile phones that emerged in the 1980s, whether car-based or truly portable, these early MTS examples were super-exclusive not just because they were super-expensive; they also had one key flaw that prevented widespread adoption. Namely, there were very, very few channels available for the service—initially, just three! So only three people in a given area could use the setup at a given time due to the limited number of frequencies on which they operated.

Though the number of channels was eventually increased to 32, that’s still a mind-boggling bottleneck for the technology, especially given the ubiquity of personal mobile phones today. Modern phones are able to get around this limitation by reusing frequencies, something enabled in part by the cellular concept itself (the details are beyond the scope of this discussion, but you can read more about it here).

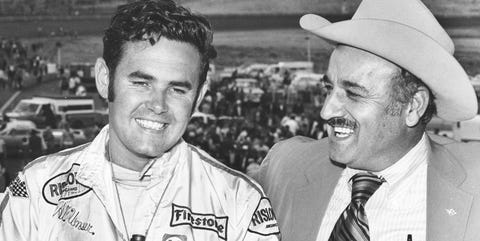

This did mean, however, that you had to be a bona-fide big shot—or at least work for a very important company—to get away with using the MTS back then. Somebody had to keep those truckers truckin’ and that earth-moving equipment movin’ after all. And with a Bell MTS setup on your desk, and your lackeys just a phone call away no matter where they were in the field, that somebody didn’t have to be you. Provided they were within line of sight of one of the receiving towers, anyway.